"I Will Make You a Billionaire"

The Friday Column: Chasing the "Two Amigos" in Riyadh, My Turn as an Opec 'Flaneur,' and Inside the Secretive, High-Stakes, Cut-Throat World of the Commodities Traders: "I Will Make You a Billionaire"

With Hugo Chavez to my right and Mahmoud Ahmadinejad just a few steps away, I knew this was not your typical oil industry conference.

The year was 2007, and I was attending an OPEC heads of state summit in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. There have only been three such summits in history: the first in Algiers in 1975, the second in Caracas in 2000, and this one in Riyadh. For oil industry folks, this was the Super Bowl, the World Cup, and the Olympics rolled into one.

Both Ahmadinejad and Chavez were riding high as oil prices soared, and they clearly had a strut in their steps. One attendee recalled Chavez in particularly fine back-slapping spirits, crying out “Ole! Ole! Ole!” to crowds that gathered around him. Ahmadinejad, too, seemed to relish the attention he was getting from the press - to no one’s surprise.

Other than the “Two Amigos” - Ahmadinejad and Chavez — a who’s who of OPEC heads of state, global energy CEOs, and oil industry leaders were in attendance. There were also several tiers of visiting delegates from the specialist and academic community, including your humble correspondent. I was decidedly on the lowest of the low rungs - my dinner table seat at the closing dinner for about a thousand people was in the protocol equivalent of Siberia.

This suited me just fine. I had no formal duties to present or moderate panels, so I could be something of a flaneur - that 19th century figure from Parisian novels that walked the streets observing all around him. I was an ‘OPEC flaneur’ minus the waistcoat, cane, monocle and twirling mustache.

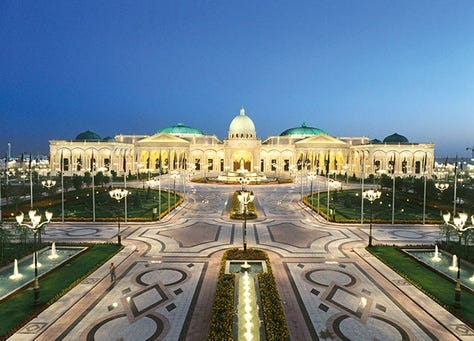

The event was long on pomp. After all, along with the Venezuelan and Iranian presidents, all OPEC heads of state were in the room - and what a room it was: a cavernous, chandelier-dripping, gold-glowing dinner ballroom at the King Abdulaziz International Conference and Exhibition Center (the view from the entrance below).

At the closing dinner, I was a good pair of binoculars away from a glimpse at the head table, but a couple of things I remember vividly: the heavy silverware with the Saudi two sword and palm tree crest on them, and the orchestral precision of the waiters serving the hundreds of tables.

After the dinner, journalists and delegates milled about in yet another cavernous room dripping with chandeliers and gold as the heads of state and their retinue rolled out to their waiting cars (yes, they were black sedans with flags on their fronts.) Most of the leaders made a dash for the exits, except for two: Hugo Chavez and Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. Not known as retiring fellows, they both waded into the crowd of journalists and delegates, and held court for about fifteen minutes, responding to questions.

Both leaders had made some noise at the conference when they blasted the U.S dollar as weak, calling for OPEC to delink oil sales from the dollar. Ahmadinejad declared that “the U.S dollar has no economic value” and Chavez went “full Chavez” when he said: “The fall of the dollar is not the fall of the dollar — it’s the fall of the American empire” (The dollar is still kicking and strong, though the same cannot be said for the legacies of Chavez and Ahmadinejad).

I flitted between the two leaders and the crowds, watching them holding court. They each smiled a lot, wagged their fingers a lot, and I honestly thought both could have stayed there all night, reveling in the attention, if their delegations had not quietly signaled them to get moving.

Over the two days of the event, I heard several formal speeches, engaged in small talk and industry talk with attendees and watched lifetime achievement awards given to industry insiders. What I witnessed on those days were the political theater of OPEC - not the insider mechanics of the oil industry.

Among the attendees at that summit were none other than Daniel Yergin, the great chronicler of both the political theater and the insider mechanics of the world of oil, gas and energy for our age. Many of you have likely read Yergin’s classic, The Prize: the Epic Quest for Oil, Money and Power, or The Quest: Energy, Security and the Remaking of the Modern World. (I am currently halfway through Yergin’s latest epic, The New Map: Energy, Climate and the Clash of Nations.)

He writes so well of the intersection of geopolitics and energy, the rise of OPEC and the national oil companies and the world of the big name brand energy majors: Exxon, BP, Shell, and on and on. Three years ago, I caught a glimpse of Yergin’s meticulousness. After I cyber-introduced him to a friend who had written a Phd dissertation on Saudi-Iranian relations, I was cc’ed on their exchange of emails: Yergin digested the massive tome in short order, wanting to know more, firing back a few emails asking about particular footnotes deep into the texts (Note: I asked Yergin’s permission to tell this story before writing it here, and he ok’ed it).

While a who’s who of the oil industry attended that 2007 OPEC summit, I’m willing to bet that there were some critical players that gave it a pass: namely, the top commodity traders. For years (decades, really), the world’s commodities traders have worked in the shadows, keeping the global economy humming by quietly moving grains, metals, agricultural goods, and, yes, oil and gas to markets around the world.

Those commodities traders were not interested in political theater; they were - and are — interested in making money. But their world makes for dramatic theater, and an extraordinary new book by Javier Blas and Jack Farchy delivers the drama: The World For Sale: Money, Power, and the Traders Who Barter the Earth’s Resources. If Yergin gives us both the political theater of the energy world as well as the insider mechanics, Blas and Farchy take us deep into a corner of a world that is rarely seen: the commodity traders that are, as they write, “the last swashbucklers of global capitalism” who are “willing to do business where companies don’t dare set foot, thriving through a mixture of ruthlessness and personal charm.”

The book launches with one of the great charmers and entrepreneurs of the commodities world, Ian Taylor, the CEO of Vitol on a, well, swashbuckling mission: providing fuel to Libyan revolutionaries in 2011 in the early days of the uprising against long-time dictator Muammar Gaddafi. Taylor, the authors wrote “had transformed Vitol from a mid-sized fuel distributor to an oil trading giant” that today handles “enough oil every day to supply Germany, France, Spain, the UK, and Italy combined.” (Vitol just this week announced a $3 billion profit on its 2020 books: what pandemic?)

So what was Ian Taylor, by then already a fully-fledged member of the British establishment with a Rolodex of contacts that would make a head of state envious, doing flying a private jet into a war zone? Well, there was money to be made. Oh, and Qatar — who were backing the rebels — asked him to do it. The book is full of those kind of geopolitical twists.

The authors note that the Vitol mission changed the course of history. “Without $1 billion of fuel in their moment of need, the rebels would have certainly been defeated,” they write. Without that fuel, Muammar Qaddafi may never have been pulled from a drain pipe and killed by an angry mob.

I thought a lot about this idea of traders changing the course of history as I read the book. There is certainly truth in that idea (South Africa’s apartheid regime would have buckled under sanctions sooner had not many of the amoral traders been willing to provide them with supplies) but the deeper I got into it, I realize there may be something else at play: the traders are also the ultimate surfers of history, riding the waves to their advantage.

The authors point to four key developments that super-charged the macro environment for the global commodities traders: the nationalizations of several Middle Eastern oil companies in the 1970s; the collapse of the Soviet Union; the China-led commodity boom in the first decade of this century; and the financialization of the global economy beginning in the 1980s.

“I Will Make You a Billionaire”

All of these developments offered an opening to commodities traders, a wave to surf if you will — and they rode those waves with gusto. Who were these history-making “surfers”? Legendary (and sometimes notorious) figures like March Rich, Ian Taylor, and Ivan Glasenberg get a lot of air time in the book, but also lesser-known figures like the metals trader David Reuben who parlayed his contacts in Russia’s “wild east” of the early 1990s to become an aluminum king. Reuben famously told a visitor from Central Asia who came to his office with news of where to buy aluminum: “Show me, and I’ll make you a billionaire.”

But doing business in the ‘Wild East’ was not for the faint of heart. There were murders, pay-offs, threats, mysterious accidents, and a typical day looked like this for the trader in search of aluminum, according to Blas and Farchy:

“They would hire whole jets for $20 an hour, loading up with cases of cigarettes and Johnnie Walker whisky, the only currency they could use to buy fuel at remote airports in struggling Siberian towns. They’d arrive at vast mines and smelters where the Soviet-era bosses - known as ‘Red Directors’ - would start morning meetings with a glass of vodka, or several.”

The book is full of these kind of rich anecdotes, often involving the notorious Marc Rich. A couple of gems: Marc Rich’s firm set up a fake Burundi oil purchasing company and sought lower-priced deals from Middle East producers in the name of “Third World solidarity.” The trick worked, and Rich got cheaper oil to sell at a higher price on global markets, a few Burundian officials got their pockets lined, and everyone went their corrupt ways.

Or there was the time in the early 1980s when Jamaica’s Minister of Energy woke to realize that his government had run out of money and his country would run out of oil in a few days. Who do you call? Marc Rich, of course. “What the hell are you waking me up at 2 o’clock in the morning for?” Rich reportedly said. Well, the minister replied “it’s just a small matter of life and death.” Rich said he would take care of it.

An hour later, a tanker full of Venezuelan crude headed for the US east coast changed its direction to make a stop in Kingston, Jamaica. Twenty four hours before Jamaica had run out of oil, the tanker steamed into port. Without that oil, “I think it would have brought the government down, quite frankly,” Hugh Hart, the Jamaican minister, told Blas and Farchy. Rich mined the “goodwill” generated by that deal for years of Jamaica profits afterward.

The ABCDs and the New Commodities Stars?

Blas and Farchy also take us inside the big grain traders, the so-called ABCDs - Archer Daniels Midland, Bunge, Cargill, and Louis Dreyfus. These trading houses supply us with everything from our morning cereal and coffee to everything across the agri-business supply chain. These companies have also minted dozens of billionaires in the process.

Blas and Farchy do an extraordinary job of taking us deep into these worlds of traders, and the extraordinary might they wield. As they write, “a large share of the world’s traded resources is handled by just a few companies, many of them owned by just a few people.”

As talk of a new commodity supercycle looms, the commodity billionaire of tomorrow might be the ones that got in early on copper or cobalt or lithium - the engines of our future global economy. I wonder if someone, somewhere, is offering to make a young man or a woman a billionaire if they show them to this new promised land.

*************************************************************************************************************

Fellow Travelers and Subscribers: Thank you for reading this site and my inaugural Friday column last week: Shanghai, Mumbai, Dubai or Goodbye. I was delighted to spark a conversation. Some of you have reached out with your own Johnnie Walker stories from Baghdad to Beijing (I love it; keep ‘em coming. I’m half-seriously thinking of doing a regular round-up of “Johnnie Walker in the emerging markets” stories!). You can always reach me on LinkedIn, or on newsilkroadexchange@gmail.com. (Today’s “Friday column” landed in some of your inboxes on Thursday, but others on Friday, depending on where you are in the world).

One correspondent asked me about “borrowed nostalgia” and “real nostalgia” from last Friday’s column, which led me to think: do you have a place that you look back on with misty eyes? A favorite cafe in Beirut perhaps? A newspaper kiosk in Buenos Aires? Maybe a shop on Edgeware road in London or Westwood Avenue in L.A? An Umm Kalthoum or Edith Piaf song? Something that evokes nostalgia of a place and times gone by.

If so, send it our way, and we’ll gather some for a future column on nostalgia.

Please also send us books, articles, serials that caught your eye over the week, and we’ll include in the “What We’re Reading, Hearing (Overhearing) and Watching” section (below)

What We’re Reading, Hearing (Overhearing) and Watching

The world has been full of protest this past decade. The SAIS Review of International Affairs, the student-edited academic journal that gathers some of the top thinkers on world affairs as contributors, has just launched an excellent issue on our decade of global protest. Check it out here, at the “The Revolution Will Be Televised": A Decade of Global Protest.” Well done, SAIS Review editors.

Is the China Debt Trap a Real Thing? Cobus Van Staden, co-host of the excellent China in Africa Podcast (a must-listen) doesn’t think so, but he also notes that, “like a vampire that just won’t die, we keep burying it, but it keeps rising from the coffin.” An excellent piece on the real story of the China Debt Trap. And while you’re at it, follow our Emerging World ‘fellow traveler’ and China in Africa co-host Eric Olander on Twitter, LinkedIn, or wherever you get your social media (he’s super sharp), and subscribe to his China in Africa Brief. It’s very well-reported and written and expanding to the broader emerging markets and South-South story as well.

Watch the ever brilliant Hannah Ryder, CEO of Development Reimagined, talk about how African countries should approach China: Hint, develop a strategy and declare your priorities. It’s a 4 minute video and well worth watching.

The Syria War has produced many villains, and a few heroes. Lina Sergie Attar, founder of The Karam Foundation, is one of the heroes. We’re reading her moving essay in Newlines Magazine “When Assad’s End Comes”, where she writes: “I dream of my country where no Syrian child or person will ever be forced to answer one name and stand under one portrait out of fear. I dream of a classroom with 100 Syrian children who are asked, ‘Who is the hope for the future of Syria?’ Each of them will stand and answer — without doubt or hesitation or fear and with all the pride we were never allowed to feel — ‘I am.’”

Journalists like Arwa Damon, Anthony Shadid (may he rest in peace), Kareem Shaheen and so many other ‘nameless’ fathers, mothers, sisters, and brothers (more to come on them) are also heroes. I read brother Kassem Eid’s book last year and have enjoyed many an evening in his company. He is truly a hero. This week, we’re reading Arwa Damon’s and Kareem Shaheen’s powerful commentaries on Syria - Arwa’s piece, Kareem’s piece.

We’re also just reading Newlines magazine in general - a powerful new addition to the Middle East political analysis and reportage world. In case you missed it, Newlines also published this moving essay reckoning with the “The Arab Spring” by the lyrical and erudite Hisham Melhem.

Fellow traveler Kamran Bokhari also just published an important essay in the Wall Street Journal entitled The Hole in Biden’s China Strategy: Central Asia.

And I have not yet read, but look forward to reading my SAIS colleague Kent Calder’s newest book, Global Political Cities. If you are familiar with Kent’s superb work on Japan, S. Korea, East Asia, the New Silk Road, Middle East-Asia energy ties, Singapore and more, you know that his latest offering will likely explore a vital contemporary trend through the lens of history, politics, economics, and commerce (more on his book later).

*****************************************************************************************************