Mike Tyson, Gray Rhinos and the Covid-19 Punch

While the US, China, and Europe show signs of recovery, the pandemic has left a trail of destruction in the developing world. Will these be generational scars?

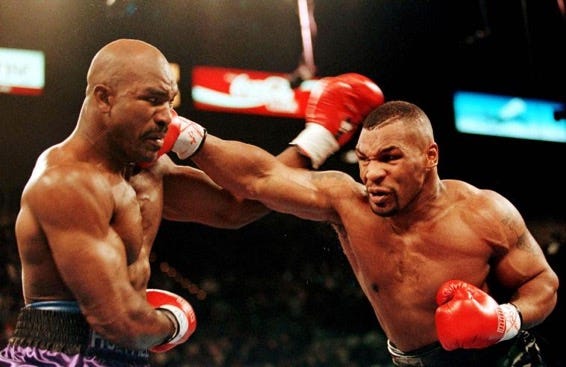

The great American boxer Mike Tyson famously quipped: “Everyone has a plan, that is, until you get punched in the face.”

The Covid-19 pandemic has been a massive punch into the face of the globe. Every corner of the world was affected. With nearly 3.5 million deaths, more than 100 million jobs lost worldwide (and the equivalent of 400 million job losses due to drastically reduced working hours), industries and businesses cratering, inequality rising, tensions boiling, and societal cracks widening from rising mental health issues to increasing political polarization, we are still woozy, reeling, and on the ropes from the Covid-19 punch.

While the numbers describe a hopeful vaccine-led economic recovery in the United States, much of Europe, China and a few Asian economies, large swathes of the world — particularly developing countries — face a long, uphill road back to normalcy.

A recent Wall Street Journal article by Joe Parkinson soberly outlined the bruises, blood, and long-term damage from this Covid punch. It’s a bracing piece that fuses together many of the harrowing data points that reflect the destruction wrought by the pandemic in the developing world. While these pages are often devoted to telling the unheralded stories of an emerging world on the rise, we must face our Gray Rhinos - highly probable, high impact yet neglected threats - as author Michele Wucker reminds us.

“Kin to both the elephant in the room and the improbable and unforeseeable black swan, Gray rhinos are not random surprises, but occur after a series of warnings and visible evidence,” Wucker writes. The post-pandemic economic havoc in the developing world and the inequality of recovery surely qualifies as one.

While several rich countries are showing signs of rapid recovery, in the developing world, “economies are falling further behind, struggling to rebound from last year’s record contraction,” Parkinson writes. He points out that two of the world’s most positive trends over the past two decades — a rising middle class and significant poverty reduction — have taken a turn for the worse in 2020.

“This has become the inequality virus,” Amina Mohammed, deputy secretary-general of the United Nations, was quoted as saying in the piece. “The diverging world we’re hurtling towards is a catastrophe.”

Further compounding the catastrophe has been the years of gains that have been lost by the pandemic’s effects. As I have written elsewhere, the defining feature of our contemporary age has been the rise of the emerging world fueled by rapid urbanization, unprecedented connectivity, declining poverty, and growing middle classes (Note: if you click on the link, I also used the Mike Tyson quip back then in 2018, but I did not foresee this kind of punch).

The so-called “rest” that comprises some 85% of the world’s population across Asia, Latin America, Africa, and the Middle East are full of dynamic entrepreneurs, world-class businesses connected to the global economy, top scientific and technological minds, and increasing pockets of good governance. Still, some of the hardest-hit regions have been in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, knocking back decades of gains.

As Parkinson writes, “until the economic shock of the virus and lockdowns, the 21st century had largely been a story of the developing world reducing the gap with the developed world in terms of wealth, education, health and stability.”

The year 2020 marked a break from that, and my worry is that the scars have run so deep that it will take several years to get back to where we were pre-pandemic.

Latin America was hit particularly hard. The region saw its worst downturn since 1821, Parkinson notes, a time when “the region was immersed in independence wars.” As more get vaccinated, we’ll see a robust recovery, but long-term problems remain. Parkinson writes, “In Latin America, well over 100 million children—more than half the total—are out of school, and many are unlikely to return, raising fears of a generation losing the benefits of education.” These are generational scars or, as Unicef put it, an “unfolding generational catastrophe.”

What about the great poverty reduction story? This has been one of the most hopeful and unheralded stories of our modern era. Since 1990, more than a billion people have been lifted from extreme poverty. That’s worth repeating: more than a billion people have been lifted from the crushing weight of extreme poverty.

But the World Bank notes that up to 150 million people could fall back into extreme poverty as a result of the pandemic. This is the first rise in global poverty numbers in two decades.

Parkinson also notes that “the pandemic has led 34 million people to the brink of famine,” which represents a record 35% annual rise. Supply-chain problems could put Nigeria on the brink of a famine, the article notes, and hundreds of thousand of people in Madagascar are starving, “resorting to eating swamp reeds and tree bark to survive.” In Brazil, “19 million people—1 in every 11 citizens—are going hungry, nearly twice as many as in 2018,” and food prices are rising.

Ominously, Parkinson also notes, “Anger over surging food prices—so often the harbinger of political change throughout history from the French Revolution to the Arab Spring—is starting to translate into violent street protests from Colombia to Sudan.”

This is a geopolitical point worth watching. Even before the pandemic, we seemed to be on a razor’s edge across the world. A modest price rise in metro fares in Chile led to massive unrest in October 2019. A month later, a suggested Whatsapp tax in Lebanon triggered widespread protests against the government. That same month, a gas price hike spawned anti-government protests across Iran. More recently, protest against a police unit in Nigeria and a proposed tax overhaul in Colombia unleashed a torrent of protest in both countries.

In many ways, these protest movements were not simply about metro fares or WhatsApp taxes or gas price hikes or violent police or tax overhauls. They were driven by frustrated populations, driven to that thin line between despair and defiance by years of mismanagement, corruption, and bad governance. Let’s face it: for all of the hope of the emerging world over the past few decades, those pockets of good governance still remain pockets and they need to grow much more rapidly and broadly to deliver the better future so many deserve.

Consider some of the damage in Africa, once dubbed unfairly by the Economist magazine as “the hopeless Continent” in 2000 before going on a decade run of growth lifting millions from poverty and growing a middle class. Today, in central and west Africa, as Parkinson writes, “cash-strapped governments are struggling to contain a resurgence of infectious diseases like measles and malaria, which have killed thousands of mostly young children in recent months.”

Meanwhile, rising African middle classes - another unheralded but promising story of our era - have also taken a hit. As Parkinson writes, “Sub-Saharan Africa’s middle class—around 180 million of the 1.3 billion population—is estimated to have shrunk by 11% in 2020, according to World Data Lab, a research organization. This year it could shrink at a similar rate, with sub-Saharan Africa set to be the world’s slowest growing region in 2021, according to the IMF.”

In addition to governance issues of their own, exacerbating the problems in the developing world has been the lack of access to vaccines. As Parkinson writes, just 0.4% of the 1.5 billion population of Africa has been fully vaccinated.

“The vaccine gap between rich and poor is now at its most severe since immunizations against Covid-19 started at the end of last year, according to investment bank UBS. Europe and North American vaccination rates generally range from 30% to 50%,” Parkinson notes.

The school closures have been particularly damaging across the developing world As more classrooms moved to online tools, more than 800 million students have no access to a computer, the report notes. “Much higher dropout rates in lower-income countries mean millions of children will never go back to the classroom.” (School closures have also hit lower-income communities in advanced economies much harder as well, exposing the inequality gaps of the Zoom have’s and Zoom have not’s.)

Again, these scars feel generational, rather than temporary.

Meanwhile, asset prices seem even further disconnected from street reality. Perhaps recent pull-backs in frothy markets will also pull back the curtains on the enormously destructive human toll of this pandemic.

The world has demonstrated tremendous resolve in tackling the generational issue of climate - another Gray Rhino. From private sector initiatives to government mandates and international cooperation, few issues have mobilized as much energy as reducing emissions.

But what could be more important today than tackling the human toll of the pandemic? Similar energy and resolve is needed to tackle our generation’s most pressing challenge now.

To receive this weekly column, plus a daily Emerging Markets round-up, and occasional thought leader interviews