Putin's Bomb and the Global Shrapnel

When Russian forces drove into Ukraine, the action set off a bomb in our global order. Beyond the Ukraine tragedy, the shrapnel will hit every corner of the world - including Russia itself.

Russian President Vladimir Putin’s brutal invasion of Ukraine set off a bomb in our global order. The question on all of our minds is: Where is all of this headed?

First and foremost, there is the tragic human toll in Ukraine. Bucha. Mariupol. Kyiv. Cities little known to most of the world have now become symbols of war crimes, tragedy, and courage.

Beyond this immediate human impact, there is the feel of tectonic plates crunching, of certainties crumbling, of history spinning a new web that will entangle us all.

That old, pithy quote from Lenin is back, making its way through Twitter and chat rooms: “sometimes decades pass, and nothing happens. Then, weeks pass, and decades happen.”

I remember seeing that quote trotted out during another seemingly historic moment - the Arab Uprisings of 2010-11. But this is obviously different. This feels 19th century - land grabs and diplomats huddling and soldiers marching through the cold. But, of course, this is the 21st century, so the tools of our era — from ballistic missiles to drones to social media to sanctions — are also shaping the outcome.

What to make of these “decades” happening over the past two weeks? Of Putin’s gamble? Of Putin himself? After all, this was a leader, the pundits told us, who may be brutal, but he was ‘savvy’ and ‘clever,’ the sort who may set a fire (ask the citizens of Aleppo of Putin’s fire), but not get singed. He is certainly feeling the heat now — even as his forces continue to rain fire on Ukraine.

How long can this last? Where will this end? Will the conflict metastasize? This leads to the ultimate question: are we on the verge of World War III? These are questions almost impossible to answer, so I will not, dear reader, abuse your attention with my idle speculation. Not only is there fog in war, but there is fog in the minds of key leaders who, ultimately, will drive this war.

So, absent going into Putin’s head, I’ll explore some trends as I see them — and humbly extrapolate where they may lead us. In short, the second and third order effects of Putin’s gamble — the flying shrapnel from his bomb — will shape our world in the short and medium-term, fueling greater instability worldwide, exacerbating inequalities and posing challenges to established leaders everywhere.

First, let’s start with inflation. Commodity prices are skyrocketing. We’ve either hit historic highs or close in a range of commodities vital to our global economy. Oil and natural gas, of course, but also nickel and copper and platinum and palladium and wheat and sunflower oil and palm oil and on and on. All of this is piling inflationary pressure on economies still reeling from Covid.

Let’s look at fossil fuels - oil, natural gas, and coal. Why start with fossil fuels? Because they remain essential to our global economy, to how we consume and connect and live - no matter what its critics say. They still make up some 83% of the world’s energy needs and produce more than 60% of global electricity. So, when crude rises, inflation is not far behind.

We have flirted with near record highs on Brent crude, seen historic releases of petroleum reserves in the United States and Japan and Europe and Mexico and others, and the price pressure still leads us upward. If Russian crude is fully shunned (it is already partially shunned, though some still like buying Urals crude at a significant discount, notably India), we could break the 2008 high of $147 by the end of the year.

For a look at who is still buying Russian oil, see this Reuters piece .

Ehsan Khoman, the insightful Dubai-based emerging markets economist at MUFG Bank, wrote recently that oil will likely average $135 on the year. Meanwhile, several top oil traders at the recent FT Commodities Summit in Lausanne, Switzerland said oil prices could top $200 by the end of the year. Natural gas prices are also hitting highs across Europe.

Cue inflation. Cue protestors taking to the streets, angry about rising fuel and food prices. Cue stunted recoveries, or possibly even recessions.

Make no mistake, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has exacerbated global inflationary pressures, will slow world economic growth (expect IMF downward revisions for the global economy soon), and has contributed to dangerously high spikes in food prices.

It has also bolstered European unity (nothing like a shared threat to do that), reinvigorated the NATO alliance, strengthened Ukrainian nationalism, and doomed Russia under Putin to years of isolation and economic contraction and underperformance.

But, what might these events mean for the emerging world?

Let’s start with food prices. They are skyrocketing. As the FT reported on April 8, “March’s food price index from the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) rose to its third record high in a row, jumping 34 per cent from the same time last year.” This marks a 12.6% rise from February. The FAO described this as a “giant leap”.

It does not require a giant leap on our part to see the dangers ahead. Food costs make up a much higher proportion of spending in developing countries than in advanced economies. As the FT reported, “food costs account for 17 per cent of consumer spending in advanced economies,” but, “in sub-Saharan Africa, food accounts for 40 percent of consumer spending.”

Russia and Ukraine constitute only about 2% of the global economy, but their impact is much larger due to their central role in commodities that directly or indirectly affect food prices from crude oil to sunflower oil to natural gas to wheat.

Russia and Ukraine account for about one-third of the world’s traded wheat.

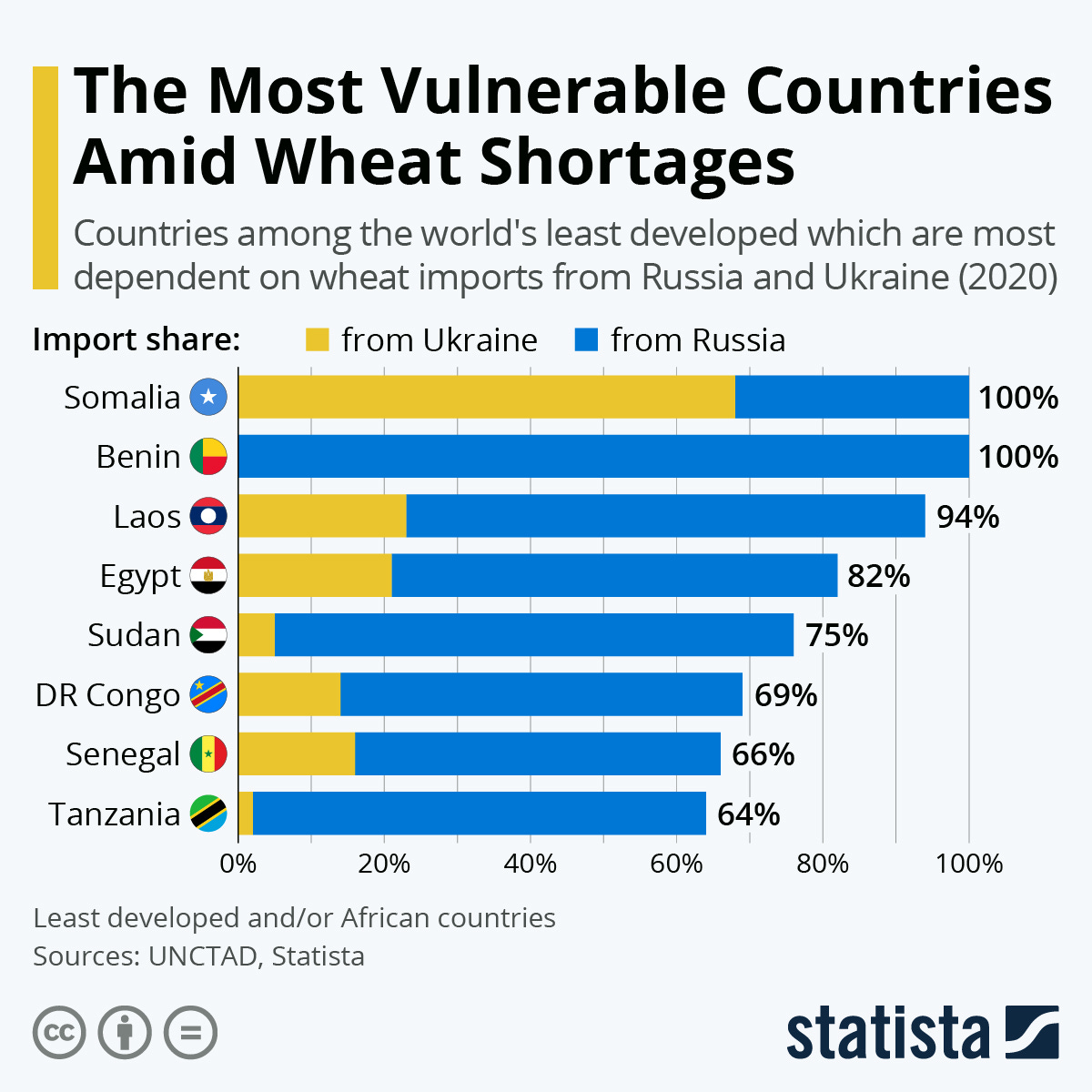

Here’s a list of countries most dependent on Russia and Ukraine for wheat

None of the above were in good economic shape before the run-up in the wheat price. Egypt is on the verge of yet another IMF bail-out. Several other Middle East, North Africa, and South Asia (MENASA) states are highly reliant on Russia and Ukraine for wheat, or highly sensitive to rising prices, including Tunisia, Libya, Lebanon, Yemen, and Pakistan. Imran Khan, Pakistan’s Prime Minister, is on the verge of losing his job to a no-confidence vote. Among the many critiques against him: failure to control rising food prices over the past three years.

Food insecurity goes beyond wheat. Russia and Ukraine also account for about 80 percent of global sunflower exports, according to FAO. Russia is also the largest exporter of fertilizers, vital to small farmers and major agri-businesses alike. Ukraine is also a major fertilizer exporter. Meanwhile, rising natural gas prices have raised fertilizer prices. Farmers are feeling the heat from Indiana to India.

Cue the farmer protests.

Other key food ingredients are hitting records from palm oil to soybean oil. This is all happening at a time when shipping prices are also soaring. All of these disruptions in the prices of basic goods and commodities are putting pressure on farmers and pinching consumers from Chile to China.

To give just one example, Sudan is facing a storm. Africa Confidential newsletter reports that inflation is running around 250% and the UN World Food Program estimates that half the population will face crisis levels of food insecurity this year. Protestors have poured into urban centers to protest rising food prices. The Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWSNET) reports staple food prices running between 100-200% higher than last year. Sudan’s military junta faces a major test. Reports have surfaced that its leaders have been actively trading gold for wheat from Russia.

Surging food and fuel prices have also contributed to unrest from Sri Lanka to Peru. From Latin America to Africa to Asia, rising food prices are challenging governments and straining populations. Even before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, rising inequality had emerged as a major issue, particularly in Latin America - the region of the world hardest hit by Covid and the one with the slowest forecasted recovery.

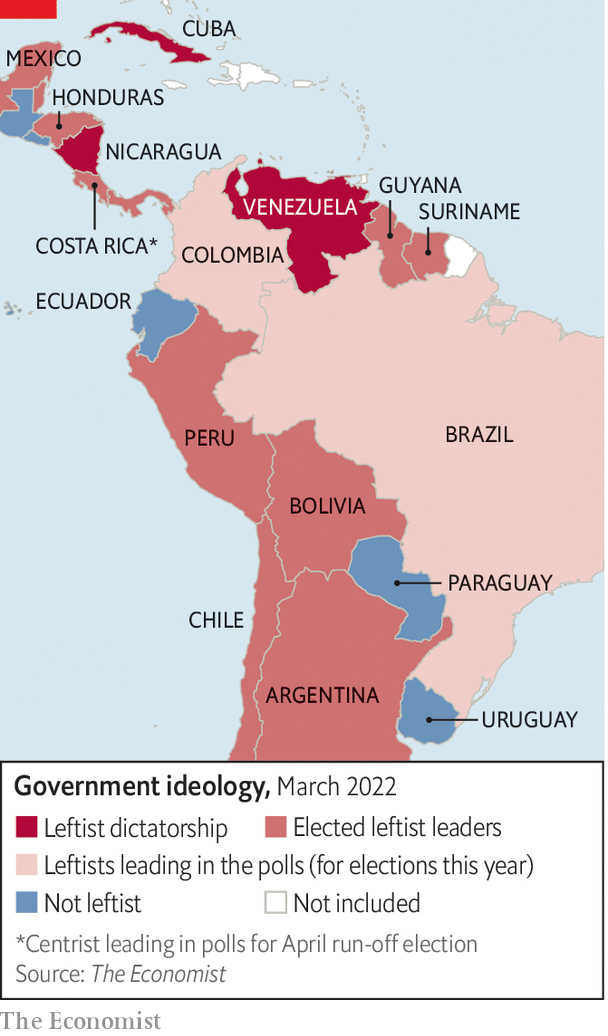

Indeed, Latin America’s recent political tilt to the left -- Mexico, Argentina, Peru, Honduras, and Chile all in the last three years — could be accelerated by current conditions. Two major elections loom. In May, Colombians will elect a new president. Traditionally, Colombia rarely leans left, but now the leading candidate is left-of-center leader and former Bogota mayor Gustavo Petro, fueled by a tide of anger about rising inequality and inflation. Petro has also pledged to phase out oil and coal production - two of the country’s largest exports. Petro, it seems, does not like petrol.

Meanwhile, in Brazil, Luiz Inacio “Lula” da Silva has a real shot at winning back the presidency in upcoming fall elections. If he does, it would mark a remarkable turnaround from disgraced and jailed former leader on corruption charges back to the Presidential house. Inflationary pressure and spiraling inequality will help his cause, though he is also tacking to the center to appeal to the business elite.

Of course, not all leftists in Latin America are cut from the same cloth. In his previous term, Lula proved to be more pragmatic as a leader than many businesses feared, and Chile’s new leftist president, Gabriel Boric, a millennial with tattoos and an Instagram account, is less Hugo Chavez, more Justin Trudeau.

Still, some of his rhetoric has already scared markets. His stated economic policies -- a mix of redistribution, social welfare, and free trade skepticism — runs against the grain of what has made Chile a regional outperformer. But Boric has an historic opportunity. Chile holds the largest worldwide reserves of lithium and copper - two of the most important metals for the energy transition. That’s like sitting on huge oil reserves in the post World War II era.

For more on Latin America’s “Pink Tide,” see this Economist graphic below

The Latin American tide had been turning long before Putin made his move on Ukraine, and the jury is still out on whether these are “socialist votes” or “protest votes,” but chaotic conditions could help the challengers in Colombia and Brazil. If Lula and Petro win, the countries with the four largest populations and the bulk of Lat-Am’s GDP — Brazil, Mexico, Argentina and Colombia — will be led by left-of-center leaders.

Finally, what of Russia? Daniel Yergin said that the days of Russia as an “energy superpower” are over. Check out Yergin’s interview on Bloomberg here below and read our Emerging World interview with Yergin here - The New World Has a New Terrain.

Yergin is right, of course, partly because of another trend at play here. Putin’s Russia is on the receiving end of a 21st century form of shock and awe from Western powers and their allies: a concerted attempt to de-globalize a country, to cut it off from the fruits of globalization.

One of the more curious aspects of the commentary following the Russia-Ukraine war has been the slew of column inches devoted to the “end of globalization” or the “slow death of globalization.” These obituaries to globalization have not come from the populist right or left, but from masters of the universe of globalization, like Larry Fink, CEO of Blackrock ($10 trillion of assets under management), or Martin Wolf of the Financial Times (whose columns are always a must-read).

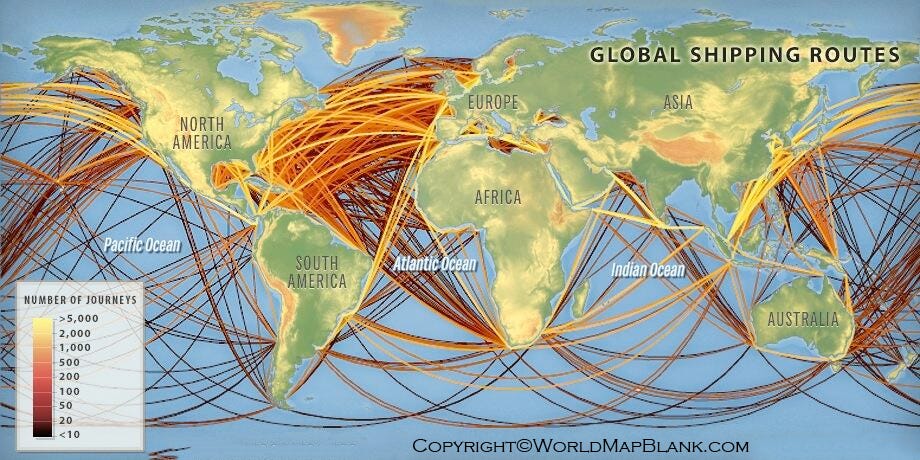

I will have more to say on this later, but let me borrow from Mark Twain, who read his own obituary in the newspaper, and wrote to the editor: “the news of my demise has been greatly exaggerated.” So, too, the news of globalization’s demise

If we define globalization as the increasing cross-border interconnection of goods, people, services, capital and ideas — and not the convergence toward Western ideas and structures, as some define it — then it remains alive and well. In a world of $28 trillion of trade (goods and services), dizzying supply chains, elaborate spider webs of air and sea connectivity (look at the flight maps of a major carrier, or the route maps of a major shipper), trillions in foreign direct investment, and tens of billions in cross-border portfolio flows every month, it’s hard to see that world crumble anytime soon.

See below: The Spaghetti Strings of Global Shipping

Also, see our Emerging World column - “The Workhorse of Globalization - The Container Ship.”

And this map from a decade ago of airline travel routes - the filaments of air connectivity, uploaded by Sarah Randolph

Air travel will likely be back to pre-pandemic levels by 2024, the International Air Transport Association says.

In a sense, the Western world’s reaction to Russia reinforces the value proposition of this form of globalization. Europe, the U.S, and allies are essentially saying to Russia: “Ok, you can invade Ukraine, but, in return, we will de-globalize you to the extent we can.” Globalization may be ending in Russia, but not the world.

Amid this de-globalization process in Russia, consider the Russian middle class, most of whom have the same simple aspirations of billions around the world: a decent home, adequate healthcare, some consumer comforts, security, opportunity, a better life for their kids.

That dream has died - along with the thousands of Ukrainians killed in Putin’s gamble.

Further Reading

I mentioned the “fog of war.” One analyst who has been excellent at seeing through some of the war fog has been my SAIS colleague, Eliot Cohen. Follow him on Twitter if you are not already doing so.

For more on fossil fuels and our world, see my column - Why Petroleum (Still) Matters).

Angela Stent’s book, Putin’s World, is one of the best of many very good books on contemporary Russia. Read her piece, “The Putin Doctrine”, in Foreign Affairs here, published before the invasion.