You Are Global

From your morning coffee to your smartphone to every aspect of your daily life, global connections and dizzying supply chains fuel our lives. You are global - and getting more global by the day.

You are global.

I am not trying to flatter (or judge) you when I say that, even though readers and subscribers of these pages are inherently globally-minded.

Even if you live far away from some of the world’s most connected cities, or if your work and life is mostly local, or if you have never traveled outside your home country, you are still global.

You are global because our world is so. I do not say this as advocacy, but as reality.

If you are reading this on a smartphone or own a smartphone like some 70% of the world’s population (roughly 5.6 billion people), then you are global.

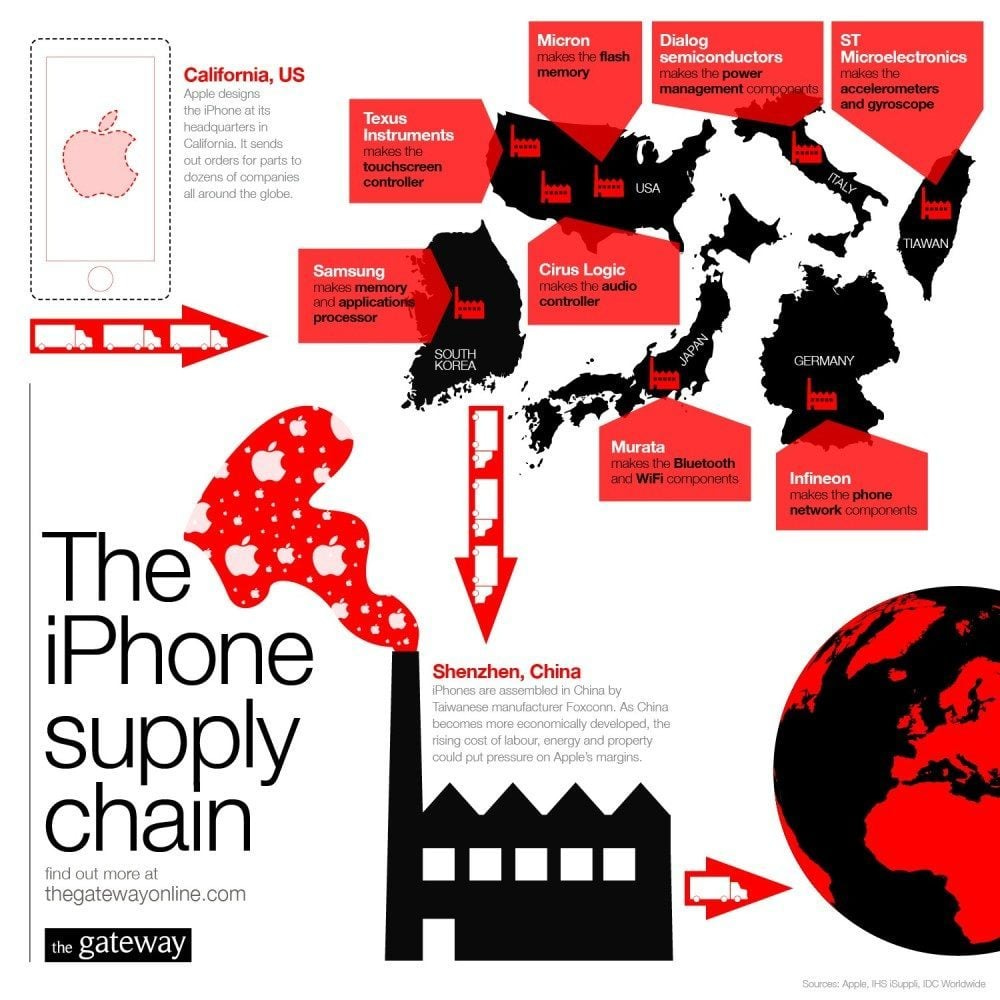

You have likely read or heard about Apple’s global supply chain, with factories in South Korea, Germany, Japan, Taiwan, the United States and elsewhere all feeding parts to the main assembly centers in Shenzhen, China to produce the iPhone. You can see a graphic of these suppliers below.

But what about the suppliers to all of these suppliers? They, too, have long and global supply chains.

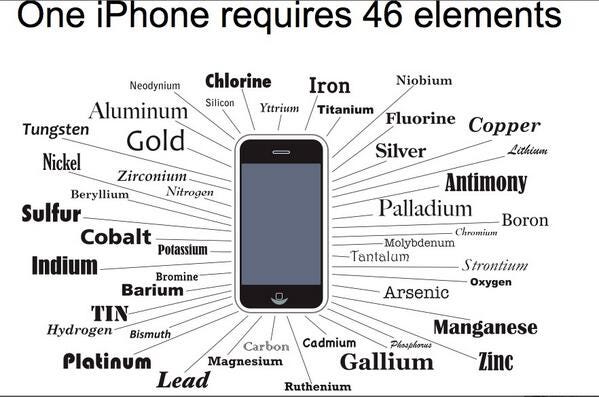

Consider only the metals needed for an average smartphone - dozens of metals that are mined, dug up, and blasted from all corners of the earth.

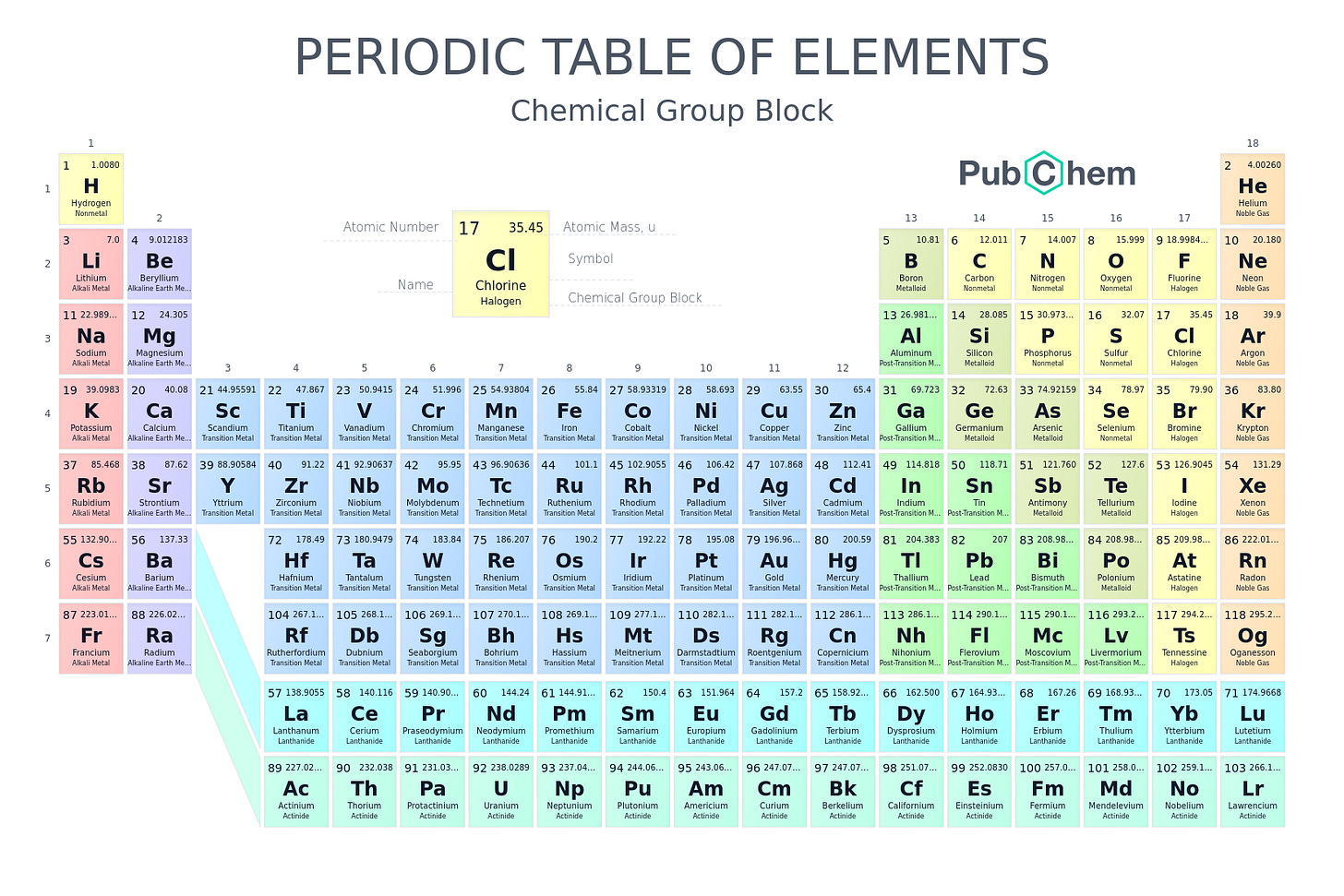

Remember this chart below from your high school chemistry class - the periodic table of elements? (Please don’t worry: there will be no quiz at the end of this article)

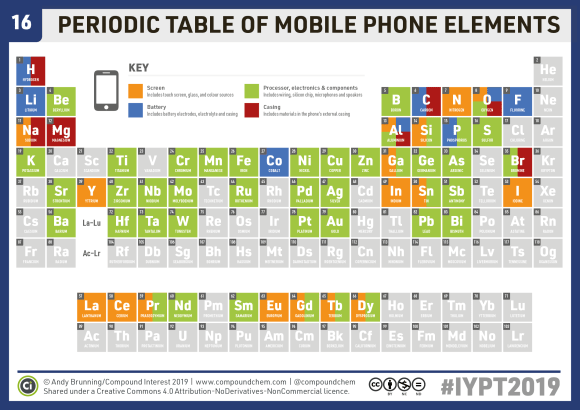

Now, take a look at this chart below. If you see green, red, orange or blue, it means that element is likely present in your smartphone.

Is there hydrogen in your phone? Yes. Lithium, check. Beryllium, check. Sodium, Magnesium? Check, check. We could go on and on. You get the picture.

The average smartphone can contain anywhere from 30-50 elements.

By comparison, we as complex humans contain only 21 of those elements.

So, where are all of these elements sourced? Well, just about everywhere on our earth.

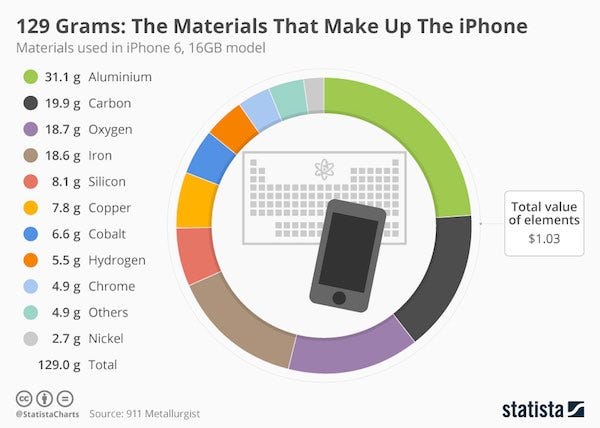

Let’s start with Aluminum. The American Ceramic Society put together a nice chart about the relative proportion of the metals in your iPhone (other smartphones have similar make-ups).

Where is the world’s aluminum sourced? China is by far the largest global supplier of aluminum, followed by India, Russia, Canada and the United Arab Emirates.

Of course, you can’t produce aluminum without its core ingredient: bauxite. The top five bauxite producing countries are Australia, Guinea, China, Brazil and Indonesia.

We could go on and on in this vein, looking at every element in a smartphone, creating a spaghetti bowl of supply chains and charts that criss-cross the globe, with resources dug up from the earth, shipped around the world, and all ending up in a Shenzhen iPhone factory.

We could also do this for so many other industries that fuel our daily lives: cars, computers, food, energy, and so much more. All of these industries are relentlessly global. The average car has some 30,000 parts, sourced from a wide range of providers across the world.

Cars also require a whole lot of metals to be dug up, mined, and blasted from the earth. The average car uses some 1500 copper wires totaling about a mile in length. Electric vehicles use considerably more than that. This is why copper demand is surging, and why electrostates may be the new petrostates.

What if you choose to purposely not be global? What if you are in the United States and want to buy the most “Made in America” cars? You might buy a Ford or General Motors brand car, right? Wrong. Actually, the Honda Passport or Volkswagen ID.4, assembled in Alabama and Tennessee respectively, are more “American-made,” according to Cars.com. Yes, the companies that make these cars may be headquartered in Japan or Germany, but these two are in the top three of the Cars.com “American-Made Index,” only surpassed by Tesla Model Y.

Many of America’s car manufacturers also export their final products around the world. America’s leading car export by value? BMW, produced in Spartansburg, South Carolina, and headquartered in Munich, Germany.

So, the next time you are at a conference and a panelist or speaker declaims something like “in this era of de-globalization” (because you can count on that lazy, overused and understudied statement said several times) remember your smartphone and your car and take a sip of your coffee and smile. In fact, look down at your coffee and marvel at the “globalization in a mug” in your hands.

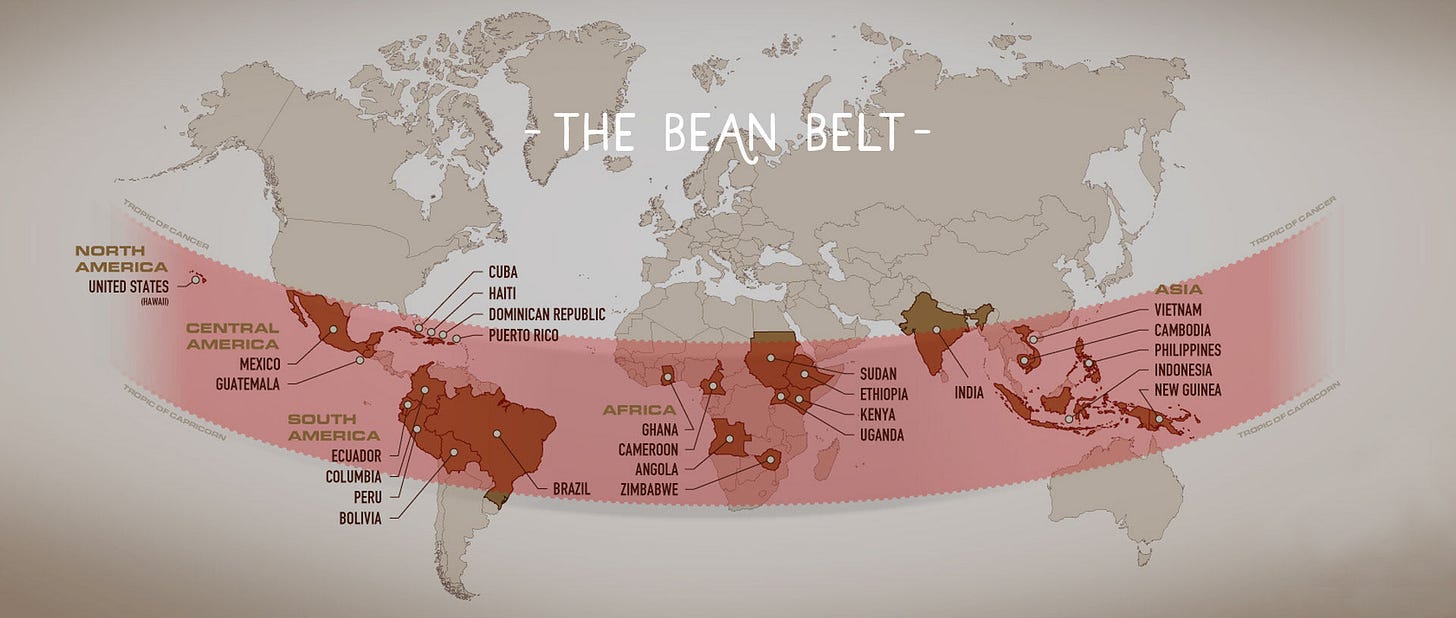

Coffee farmers are still mostly smallholders, but they feed a global business worth some $400 billion. Some 2.25 billion cups are consumed daily. Where are the coffee farmers that produce your morning (or afternoon) cup? Look at the map of the global coffee bean belt below:

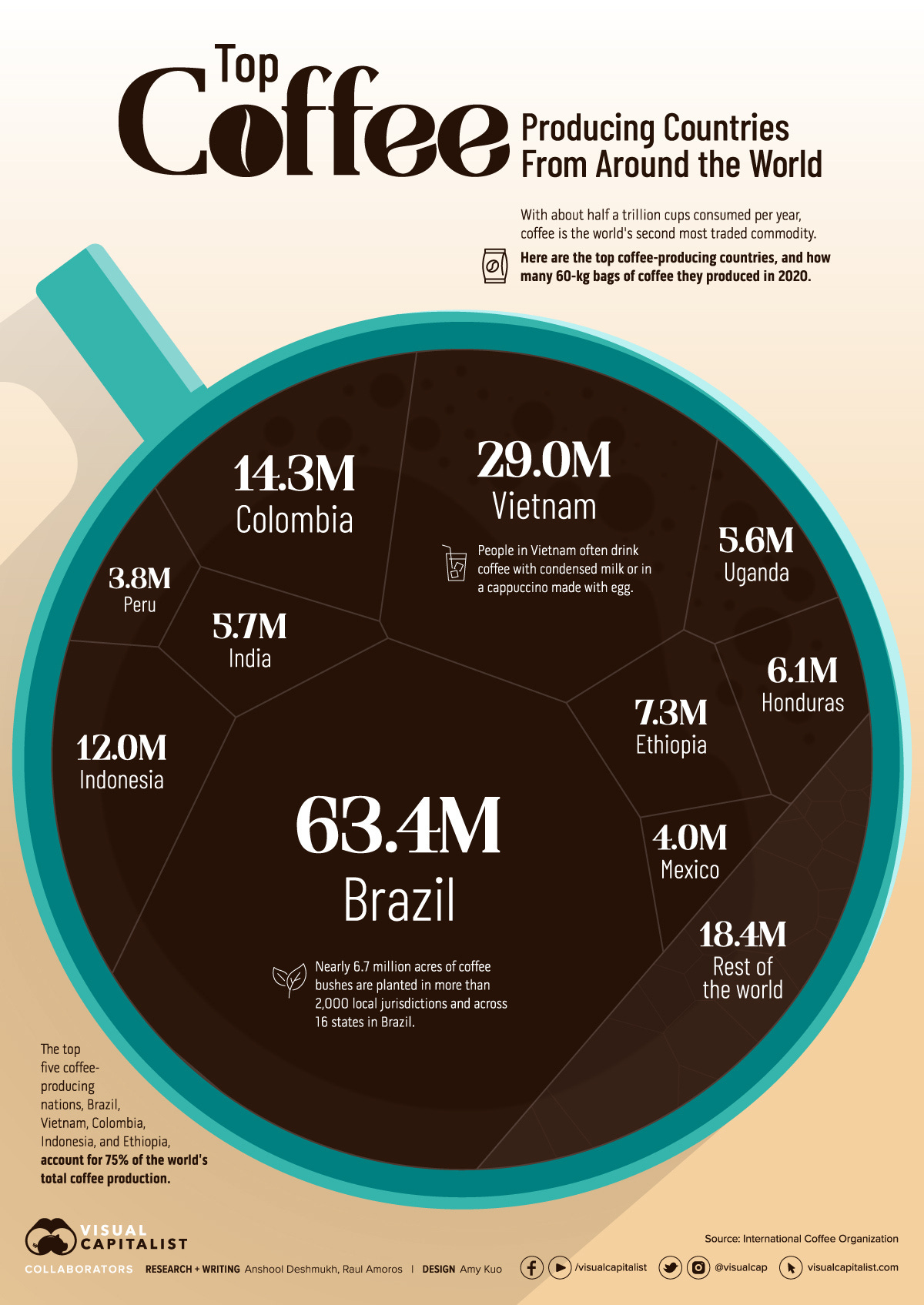

As you can see, countries in the Global South have the right climate conditions to grow coffee beans (though climate change is posing some new challenges). The biggest producers are Brazil and Vietnam followed by Colombia in a distant third. Beans from Brazil, Vietnam, Colombia, Indonesia and Ethiopia account for roughly 3 out of four cups of coffee worldwide. See the Visual Capitalist chart below.

Of course, this will not be news to most people. When we think about coffee, we generally understand that the bean comes from somewhere in Latin America or Asia or parts of Africa, but there’s a vast and dizzying supply chain of traders, brokers, commodities buyers, bankers, shippers, roasters, grocers, truckers and more that bring your coffee to your table or your local cafe.

We recognize the names of the big coffee retailers: Starbucks, Nestle, Lavazza, Keurig. We recognize the names of the major global coffee shops: Starbucks, Dunkin, Costa Coffee, Cafe Nerro, or Luckin in China. But what about the names of the major coffee bean buyers, the commodities traders mostly based in Europe, that deliver the flow of beans to the world? Companies like Hamburg-based Neumann Kaffee, Singapore-based Olam, or the Swiss-based firms Ecom Agro Industrial, Volcafe Ltd, Louis Dreyfus, or Sucafina are not household names, but they are vital to the coffee supply chain as major buyers that supply the retailers.

And what about the coffee shippers and financiers? Or the energy producers that power the shippers? And what about the international banks that power the energy producers? Oh, and the carbon emitted in all of this that contributes to global climate change…As you can see, we can go on and on in this vein.

Pick an industry and dig deep into its supply chains and you will see how global it is. Yes, there is a lot of talk of “near-shoring” and “friend-shoring” of supply chains, and there has been some modest action toward that goal, but in a world that saw some $31 trillion in world trade last year, a world in which container ships and air cargo planes still move dizzying amounts of goods around the world, capital and people are still flowing steadily across borders, and data flows are accelerating, you can see why the structures of our lives remain global.

So, the next time you are in a conference and a panelist invokes the de-globalization myth, just look around the room and play the “globalization in this room” game. The chandelier hanging from the ceiling and most of the lighting probably came from China. The carpets on the floor and the material in your chairs and the plastics in your water bottle are likely full of petrochemicals from China, Saudi Arabia, Germany, Netherlands or the United States. If you are in the U.S, the beef in your lunch likely came from cattle farms in the U.S owned by Brazilian conglomerates - two of America’s top four largest beef providers are Brazilian-owned. One of the largest American pork producers is owned by a Hong Kong conglomerate. We could go on and on.

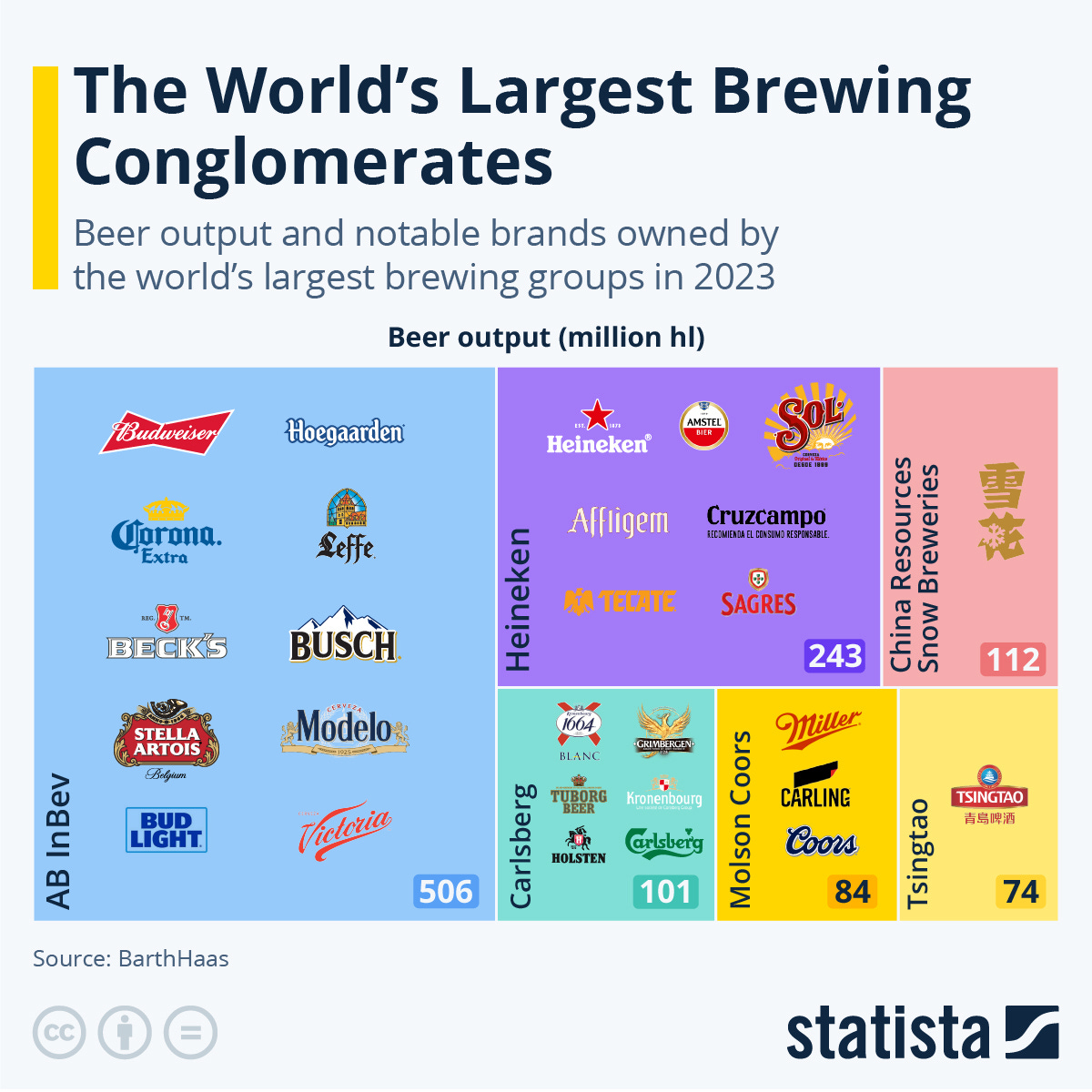

If, after all of this, you need a drink. Well, remember that your happy hour is also global. The world of beer is one of conglomerates based in Europe or China or the United States with multiple brands produced across the world. See chart below. Budweiser - that iconic “American” brand - is owned by a conglomerate based in Belgium. So is Bud Light, and it seems Mexico’s Modelo, through a complex distribution structure.

I remember giving a talk about globalization at a major investment conference and sharing a drink with some of the delegates afterwards. One of the delegates was drinking Jim Beam Bourbon, the Kentucky icon. He joked: “at least, there are still some American brands.”

I did not have the heart to tell him that Jim Beam is owned by a Japanese conglomerate, Suntory Global Spirits.

Cheers, we are all global.

Great post! Sending it to a MAGA relative.