"The New World Has a New Terrain." A Conversation with Daniel Yergin

The Pulitzer-Prize winning author talks about the new maps of energy and geopolitics, the writing process, his artist mother's influence, China-US showdown, and what he's learned as an entrepreneur

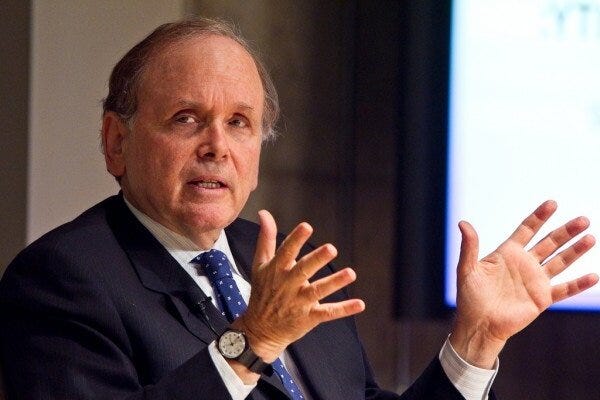

My conversation with Daniel Yergin began, appropriately, with the intersection of energy and geopolitics. After all, the New York Times called him “America’s most influential energy pundit” and Time Magazine said, “If there is one man whose opinion matters more than any other on global energy markets, it’s Daniel Yergin.” And that is exactly what his new book, The New Map: Energy, Climate, and the Clash of Nations, is all about.

But as the conversation flowed, we talked about his writing process, the role that his artist mother played in his craft, and how he has straddled the worlds of book author, academic, and private sector business leader. After all, he and a partner launched a business, Cambridge Energy Research Associates (CERA) in 1983 with a $2 purchase of a filing cabinet the same year he began writing his Pulitzer Prize-winning work on oil and geopolitics, The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money and Power.

That small company grew to be a major player in the world of energy consulting and the event they hosted in Houston - CERAWeek — was dubbed “The Super Bowl of the energy world.” Eventually, a larger global player acquired CERA and Yergin is now Vice-Chairman of that firm, IHS Markit. And yet despite a demanding job, he still writes grand tomes about our world and where it may be headed.

Like many of Yergin’s books, The New Map: Energy, Climate and the Clash of Nations, has been critically acclaimed by reviewers. NPR National Security reporter Greg Myre called the book “a masterclass on how the world works,” the Wall Street Journal called it “Supremely readable — no mean feat among geostrategy tomes,” and the New York Times called him “a master story-teller” and “one of the great chroniclers of our day.” In the Washington Post, David Von Drehle called it “a tour de force for understanding geopolitics.”

But I find that his books are not simply reviewer-friendly, but also reader-friendly, and I often recommend them to students of international affairs. It’s hard to find someone in the world of international relations that has not read one of Yergin’s books or seen his documentaries on PBS or the BBC.

His research process is meticulous. I recounted one anecdote in a previous column - “I Will Make You a Billionaire.” After I cyber-introduced him to a friend who had written a Phd dissertation on Saudi-Iranian relations, I was cc’ed on their exchange of emails: Yergin digested the massive tome in short order, wanting to know more, firing back a few emails asking about particular footnotes deep into the texts.

I suspect it’s that level of intense curiosity coupled with attention to detail that make his work so eminently readable and valuable.

Here’s some excerpts from our recent conversation in which we also talked:

World Oil Demand to 2050

The China US-Showdown

The 312th Year of the Energy Transition

Writing in a Semi Dream-Like State

“America’s love affair with the automobile may turn out to be just a hook-up.”

Balancing Worlds: Academic and Entrepreneur

The Serendipity of Business

What Business Leaders Understand: Uncertainty

Daniel Yergin

“The new world has a new terrain.”

Writing The New Map arose from the conviction that the world was changing and changing pretty rapidly. I started thinking about the physical maps of the world and how the maps of energy supply were changing the maps of globalization. It became pretty quickly a metaphor for a new world, the new terrain of energy and geopolitics.

The guiding idea of the book became to provide a guide to that changing terrain and what will be shaping that terrain over the next half decade or so. At the same time, I wanted to write a book that grips readers, tells a compelling story, with very interesting characters, and that people will enjoy reading. It’s very meaningful when one reviewer called it “a page turner”-- that for a book on energy and geopolitics!

It’s a story with multiple stories. One is how the U.S went from being the world's largest oil importer -- which has such geopolitical significance -- to the US being energy independent, which also has geopolitical significance.

And it also is about the changing relationship between the United States and China, particularly the radical change since 2015, and the risks inherent in that change. “Russia’s Map” ties energy and geopolitics so clearly together, and obviously, that is central to the new maps in the Middle East.

Then, continuing in metaphorical terms, the roadmap to the future describes the coming changes in automobiles and transportation and the impact on energy and geopolitics. Finally, I looked at the new climate map and the energy transition that is unfolding across that map. There's the world before the 2015 Paris climate conference and the world after the 2015 Paris climate conference. We are heading to a new phase with the follow-on Glasgow conference in November. I sought to bring all of this together in The New Map. I realized that ever since The Prize (Yergin’s Pulitzer-winning book, published in 1991), I’ve been writing about the relationship between energy and geopolitics. The relationship has changed a lot in the last few years and continues to change, and so I felt a real imperative to explore these new maps.

“America’s love affair with the automobile may just turn into a hook-up,” US-China strains and other seismic shifts

The automobile industry looks like it’s going to through a change that could end up a radical change. What has been called for years America's love affair with the automobile may turn into just a hookup with ride-hailing. Combine that with electric vehicles and self-driving cars, and you’re on a different road.

It has been remarkable to see how fast US-China relations have changed. I was searching for a phrase to describe what had been the relationship up to about 2015. I ended up calling it “WTO Consensus”, the view that China and the US were in this globalized world order together. But that’s not the case anymore. We’ve entered an era of great power competition and polarization.

The change in the U.S. oil position is also dramatic. There's never been a build-up of new oil supplies in terms of size and magnitude and speed, to compare to the shale revolution in the United States. It seems now to be almost taken for granted, but it's a really big and decisive change.

Something else that really stands out is the difference in the view towards energy transition issues if you're in Western Europe or North America compared to those in emerging markets. In the developing world, they remain focused on reducing poverty and raising living standards and improving health. And sometimes it appears, in the OECD world, that gets forgotten.

“We are in the 312th year of the energy transition.”

Wearing my economic historian hat, I concluded that we are in the 312th year of the energy transition. It began in January of 1709 when the world began moving from wood to coal not because it was a cheaper substitute for wood but because it enabled a metal worker to make better iron. Historically, energy transitions have taken a century or more and really become more like energy additions. Oil overtook coal on a global basis in the 1960s. But coal has grown a lot since then.

Now, the political agenda says that the world needs a radical transformation in the energy foundations of a $90 trillion world economy -- and do it in less than 30 years. That’s a pretty tall order. It has become clear that this can only happen, if it is to happen, with carbon capture. That means that oil and gas are still going to be important parts of the energy mix in the year 2050.

Think of it this way, Afshin: you recently wrote about what you called “globalization in a needle”. Petroleum products are used in making vaccines, and they are used in making medicines. Also, about 20% of an electric car is plastics, which also derives from oil or natural gas.

Today, if every car in the world was an electric car, you'd only reduce energy related human co2 emissions from their current level by about 6%.

People think it's much higher because you put gasoline in your car, but petroleum is used across supply chains. Automobile seats are made out of petrochemicals, and their production was recently disrupted by the freeze in Texas, which shut down chemical production.

So, what some expect to be a post-carbon world will still use a lot of carbon, and they’ll probably use it with carbon capture.

In India or Nigeria, for example, energy transition is a plural word, not a single word. It’s “energy transitions”. On the one hand, it's wind and solar. But on the other hand, it's also clean oil. And it's also natural gas to deal with what the World Health Organization has said is the biggest environmental problem in the world, which is indoor air pollution, with billions of people cooking with wood and waste products. And so for billions of people in the world, it's a much more difficult and challenging agenda, and more variegated, than it is just setting a goal to reduce carbon and everything else will take care of itself.

World Oil Demand to 2050

I spent a lot of time researching and thinking about the future of world oil demand. My conclusion in The New Map is that oil consumption will likely continue to increase to around 2030. And then it begins a decline, but it's not a precipitous decline. Gasoline cars on average stay on American roads for 12 years. So, in a green scenario – what we call “Green Rules” -- the world in 2050 would be using 50 or 60 million barrels a day, compared to 100 million barrels a day today.

Natural gas consumption probably continues to grow for a longer period of time, and then plateaus and declines as well. So, the energy mix in 2050 is going to be a mix, but a different mix. There will be a lot more wind and solar energy, and batteries will play a bigger role, based upon what we know today and what we can see. But oil and gas will continue to be part of it.

There's an outdoor clothes company in the United Stats that refused to put a company logo on several hundred of their jackets that an oil company wanted to buy for employees because it said it doesn't fit what they said was “our values”. The irony is that they ended up getting an award from the Colorado Oil and Gas Association as “customer of the year” because their products are made out of nylon, polyester, and polyurethane -- all petroleum-based products. And, according to news reports, the company’s management team had just built a new hanger for its corporate jet.

The China-US Showdown: Echoes of Pre-World War I?

I didn't expect to spend so much time writing about the South China Sea, but I found myself doing a deep dive into how the South China Sea became such a critical issue. I went back to the French archives and found records of three French ships that visited some of the Spratly islands in the South China Sea and hoisted French flags on them. These were virtually uninhabited islands in 1933. That led to the drawing in 1936 of what became the “9-dash line” map, which the Communists adopted as their map when they took over in 1949. It was an accidental moment that changed history, and it happened about 90 years ago. And here it is today, with the US and Chinese ships coming close to colliding with each other in the South China Sea.

So I put the US-China deteriorating relationship at the top of the list of the geopolitical issues because it starts to have these pre-WWI qualities to it, with high degree of economic integration, and people saying that conflict can't happen. But it can.

My first book was on the origins of the Cold War, Shattered Peace. I never expected to be writing another book on the origins of a possible new Cold War. But I had this rather chilling sense as I was writing The New Map about how this present situation has come about and where it may be headed. I remembered from Shattered Peace the focus on ascertaining and debating intensions in the early years of the Soviet-American Cold War. What's the intentions of the other side? And there seems to be increasing focus today, once again, on trying to assess the intentions of the other side.

Yet what makes this not a Cold War in the Soviet American sense is that these two economies are so integrated. Over 40 percent of the containers that are arrive in U.S. ports are from China. And both countries are so embedded in the world economy. All this makes the nature of the relationship between these countries the great challenge for statecraft going forward.

Leaders around the world, I find when I talk to them, say a similar thing, and I wanted to bring that out in The New Map. They don’t want to have choose between the United States and China. Both countries are central to the well-being of their countries.

The Writing Process and Semi Dream-Like States

it would be so much more efficient if I could sit down and write an outline at the beginning and just fill it in. But that’s now it works for me; the book really evolves. That’s certainly how The New Map proceeded. That process requires a total immersion in one particular part of the subject -- getting my arms around it. And then shaping it. When I was in high school, I did an interview with the well known science fiction writer Ray Bradbury, author of Fahrenheit 451 and The Martian Chronicles. He talked about writing as playing out rope from the subconscious. And it is kind of like that; you are making a deal with yourself that somehow you will figure it out without really knowing how and that you will trust yourself to get there. Someone once asked me how I wrote The Prize. The honest answer at the time was that I don’t know. I’d have the same answer about The New Map.

I look for stories and I look for the people shaping these stories and at the same time I look for the big themes and then fuse them in a narrative. I focus in one part and then another and you start to see how it all connects.

There are actually a couple deals you make with yourself. One is to rely on your subconscious, some part of your mind, to help you organize it. And the other deal you make is that, at some point, you come to closure, and you don't keep rewriting. You accept what you’ve done. I like the process of editing what I’ve written. But at some point, you have to stop. Of course, there’s the old saying that you don’t finish a book. Rather, the publisher takes it away from you. Also, as I write tend to see it visually. It's sort of like I'm watching an internal movie. And I'm writing down what I see. There is definitely a zoning-out quality to the whole process.

At the same time, I am living the story, if I may call it that, exploring The New Map, if I may put it that way, on a daily basis. I live these themes all the time. I'm seeing people and talking to them. I listen a lot, and connect things in my mind. But I also keep a separation between being an active participant and writing The New Map and the other books.

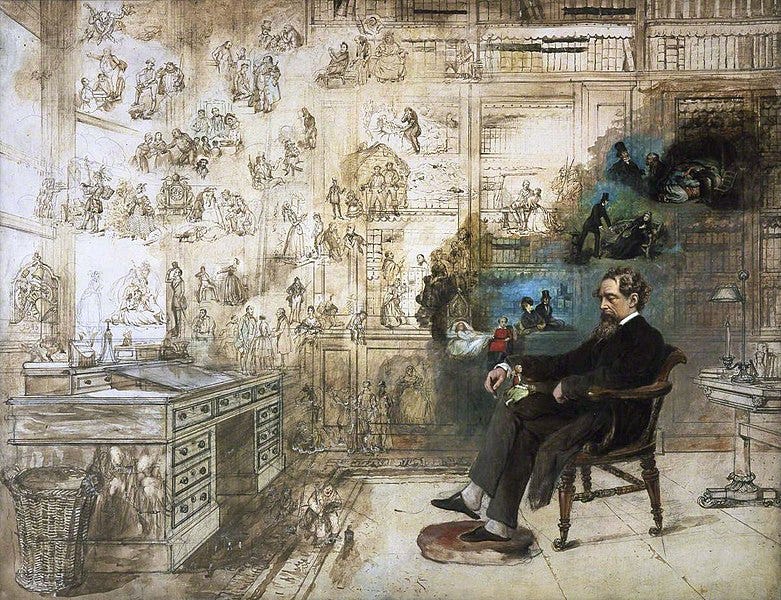

My mother was an artist and I would watch her sketch. When I write, I sketch. I sketch out this section and ask: how does this flow from that? How does this relate to that? I draw lines and circles.

Once I sketch it out in longhand, I put it in the computer because my handwriting suffers from the fact that I missed a year of handwriting when I changed schools when I was seven. I really do like the process of editing. Some people get a lot of pleasure from hitting a golf ball. I get a great deal of pleasure from getting a sentence so taut that it sings. Get the language as right as I can. I read it aloud to myself, and I ask: how does this sound? And so I will I go through a lot of drafts to do it, but it's not painful, because I enjoy the craft.

I use writing pads, but not legal pads. They are too big. It's different than composing on keyboard because you're in a different posture. If I can stretch out on the couch at 1130 at night and do it, it's going to have a different quality to it than if I did it at 1130 in the morning sitting at my keyboard.

So, I’ll start sketching and then I'll rip it off the pad, put the sketch next to me, and then write it in longhand. And I might do that two times in longhand, and then put it into the computer. And I'm not trying to write the whole chapter. It's just writing maybe eight paragraphs or paragraphs in longhand. Someone once said to me, I think, that writing a book is actually writing paragraphs. But a lot of them.

I remember reading a biography of Dickens, in which the author talked about how Dickens would be in a semi-dreamlike state when he wrote. I don’t’ mean to make that a personal comparison by any means , but I do find it’s easier to be in a semi-dreamlike state at night. It’s a more creative time.

Balancing Worlds: Academic, Author and Entrepreneur

After teaching at the Harvard Business School, I formed Cambridge Energy Research Associates – CERA – with one other person, Jamey Rosenfield, with whom I still work. It went from a two-person company with a $2 file cabinet to being part of a 16,000 person company that's about to merge with a 24,000 person company to be a 40,000 person company. So it's been quite a transition, but during that I've been able to do five books and do two PBS and BBC and NHK (Japanese) television series.

Other people say I have a pretty intense work ethic. But I don't regard it as work because I just find it Interesting. It's constantly interesting.

I have always thought that one virtue of The Prize was that I started a business the same year as I started writing The Prize. A little crazy looking back, and of course, I was five years late in delivering the book. But at some point my editor said he realized that I was going to deliver a different book from what he had signed up.

But there was a virtue in writing The Prize while creating a business that is connected with geopolitics, which was understanding that you don’t know the end point or what’s going to happen along the way. Sometimes people implicitly assume that decision makers and people in the middle of things have all the information, have enough time, and know how things are going to turn out. And what I've learned from all these years I've spent in the business world is that none of those exist. You never have enough time for decision, you certainly never have enough information, and you don't know how things are actually going to turn out. And so I've tried to capture that sense of uncertainty and contingency and suspense. “What comes next?” Nothing is preordained.

There are several great stories in The New Map that demonstrate that. There is the story of George Mitchell and the shale revolution. Everybody said it was impossible. It took him 16 years. People said: You're wasting your money. He said: It’s my money. I'll waste it if I want. As they were about to give up, it all came together – partly because someone went to a baseball game and sat with someone else by chance.

Then there’s the story of a young technologist named J.B. Straubel having lunch with Elon Musk in 2003, trying to convince him to invest in an electric airplane. Elon Musk said he wasn’t interested and so JB said: I have this other idea for an electric car, and Musk said: yes, I’m interested. Years later, Musk said that if it had not been for that lunch, there might well have been no Tesla.

All this brings home that people, no matter what their position, don’t really know where things are going, what twists and turns lay in the future. Not by any means. And that makes the story-telling all the more compelling. There’s the suspense and drama. It’s the age-old principles of story-telling. “And then…!” But it helps to have a map!

For more thought leader interviews like this, a daily emerging markets round-up and Afshin Molavi’s weekly Emerging World column - the most recent one, “Globalization in a Mug” - the journey of your coffee bean to your cup..